By PAM SMITH

Timing is everything. Yolanda and Don Hitko can attest to that. The Michigan transplants moved to Yaupon Beach the day before Hurricane Floyd slammed onto the North Carolina coast.

Its driving winds, tides and floods cut fresh scars on beaches, already struggling to heal from an earlier assault by Hurricane Dennis. Meeting little resistance, Floyd managed to wipe out many remaining dunes, pushing sand across ocean beach roads and into soundside marshes.

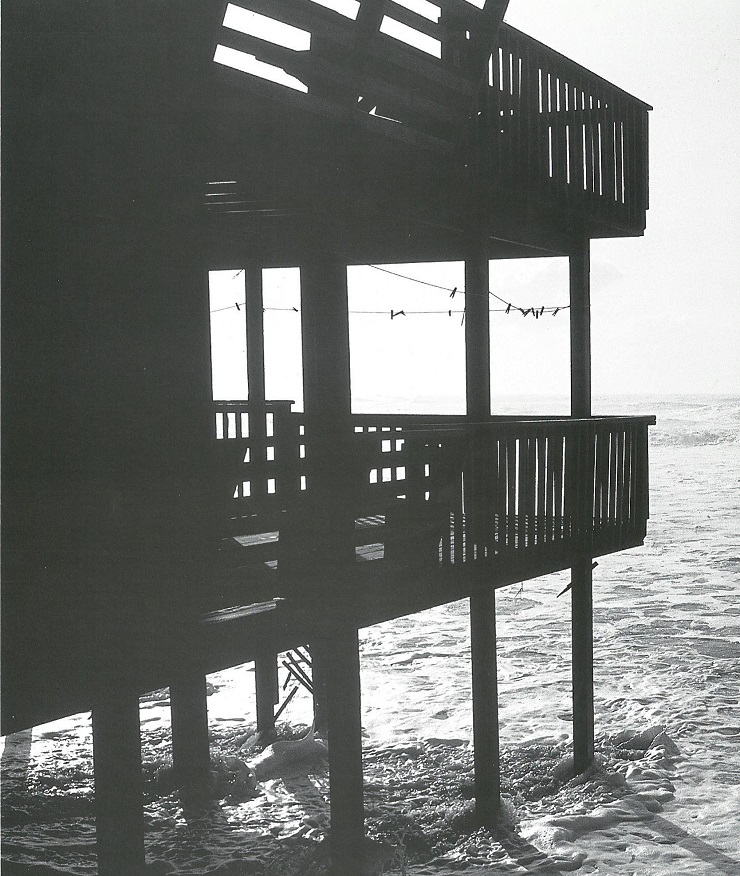

Waves crashed up the beach and scoured sand from the base of the man-made six-foot dune that stood between the advancing sea and the Hitkos’ new home. The line of dunes that runs along their property and the public access way also took a pounding.

“I believe the dunes protected us,” Hitko says. With about $25,000 worth of property damage, he feels blessed compared to many Oak Island neighbors whose homes and businesses were destroyed by Floyd’s direct hit.

Oak Island is in line for a major beach nourishment project in 2004 that will transport sand to widen its beaches and engineer a dune system along its popular ocean front beaches. In the meantime, some sand from the Wilmington harbor relocation project will be placed on part of its sand-starved shores. Traditionally, the town has redistributed sand that could be retrieved in the wake of storms.

“I am definitely a believer in beach nourishment projects and am willing to pay my share,” Hitko pledges.

But Hitko knows that beach erosion and beach nourishment are “hot button” topics that evoke as many opinions as grains of sand on the beaches he would like to see restored.

The catastrophic 1999 hurricane season heightened public awareness of the vulnerability of erosion-prone coastal communities, where beach erosion is a fact of life — nature’s work in progress.

Still, storm damage, coupled with mushrooming coastal development, seems to have been a catalyst for new pleas to state legislators for a funding mechanism to address long-term beach nourishment needs.

Coastal Development Regulations in Place

In 1974 the N. C. General Assembly passed the Coastal Area Management Act (CAMA) to coordinate state and federal programs affecting coastal land and water resources, and to promote sustainable coastal development. Among other things, CAMA seeks to preserve natural ecological conditions for the barrier dune systems and beaches, and to safeguard their economic and aesthetic values, says Walter Clark, North Carolina Sea Grant coastal law and policy specialist. CAMA established the Coastal Resources Commission (CRC) as its regulatory arm.

Well-designed and engineered dunes — with stabilizing vegetation — are essential to successful renourishment projects. Photo by Spencer M. Rogers.

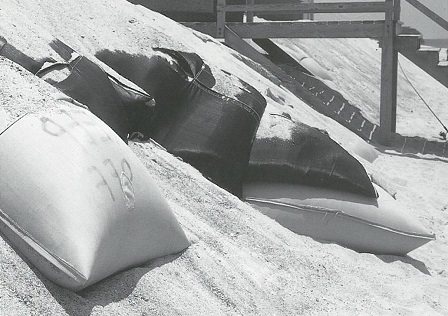

Beginning in 1985, the CRC established building setback regulations based on historical rates of erosion, averaging two to three feet per year. Building relocation and beach nourishment are the preferred CRC erosion control methods. Bulldozing is allowed as an emergency remedy in some situations, Clark explains. And sand-bag placement is permitted only as a temporary measure. Hardening measures, such as sea walls, bulkheads, and jetties, are not allowed.

Renourishment is a method of trucking or pumping compatible sediments from another source, usually from state or federal navigational dredge projects, onto the eroded beach. Bulldozing is the process of redistributing sand to provide temporary protection to existing dunes and beachfront structures. It does not add new sediment to the beach from outside sources. Each method comes with a set of environmental criteria.

For many years, coastal communities have relied on the U.S. Anny Corps of Engineers (ACOE) to design and implement beach replenishment programs. Projects must meet environmental impact tests set by CAMA and the federal government, says Tom Jarrett, engineer for the corps’ Wilmington district. “The biggest factor for a successful project is the distance we can move the beach seaward, and are able to maintain the distance,” he says. A deep, sandy strand absorbs wave energy, while dunes provide a line of defense against advancing wave action.

The price tag for renourishment varies with the scope of the project and proximity to the sediment source. Federal, state and municipal sources usually share costs. Most beach communities pay for beach rebuilding programs with part of a hotel tax. These taxes are levied by the local governments, but are authorized by state legislators.

Led by Oak Island Mayor Joan Altman, the newly formed North Carolina Shore and Beach Preservation Association wants the state and federal governments to consider a more permanent revenue structure to support renourishment projects. The group says the focus should be on the economic impact of beaches on their communities, counties and the state. Beach residents and tourists annually spend more than $8 million for each mile of beach, compared to the $1 million per mile cost for renourishment, the association asserts. Coastal-related tourism pumped about $3 billion into the state economy in 1998, according to the N.C. Department of Commerce.

Dynamic Systems On the Move

But, barrier islands are much more than economic engines to North Carolina Sea Grant researchers Charles Peterson and John Wells.

Peterson and Wells study the physical and biological dynamics of barrier islands at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences at Morehead City. In their study, “Restless Ribbons of Sand,” the scientists explain that coastal barrier islands hug 2,700 miles of our nation’s shorelines from Maine to south Texas.

The barriers absorb ocean energies and provide the mainland with a “line of defense against wind and tidal energies and especially against the ravages of frequent winter storms and occasional hurricanes.”

To understand what is happening to the barrier islands, Wells and Peterson say it’s necessary to understand something about their formation. Geologists theorize that coastal barriers formed as sea level began to rise about 18,000 years ago. Coastlines retreated and ridges of beach dunes were breached by rising water, flooding the lowlands between ridges. These ridges became barrier islands. About 5,000 years ago sea level rise slowed, as the islands migrated slowly to their present positions. Global warming could accelerate sea level rise, they say.

But sea level change is only one factor in the erosion equation. Barrier islands, they say, are part of a “sand-sharing” system. Waves strip away sand from the upper beach and dunes, moving it to the lower beach, or to the continental shelf. In time, waves may push the sand from offshore storage back to the beach and rebuild the dunes.

Sand also can be carried along their beaches. This littoral drift can transport as much as one million cubic yards each year along dynamic barriers such as Cape Hatteras. Because chains of barriers operate as a system, what one island loses another gains. Inlets that separate the islands often are traps for transporting sand.

The barrier islands also can be reshaped during a storm surge when waves wash over the entire island, dumping the sediment as far as the sound side of the island.

Peterson and Wells are evaluating erosion mitigation methods. They are examining the effectiveness of bulldozing and its impacts on biological resources. Focusing on Bogue Banks, they are studying the impact on shore birds, surf fishes, macroinvertebrates and nesting sea turtles.

Looking at the Sand Beneath the Surface

Most people are surprised to learn that sand is not an infinite resource along the coast, says William Cleary, professor of geology at the UNC-Wilmington Center for Marine Science.

Atlantic Beach received sand from the Morehead City port dredging in the mid-1990s. Photo by Spencer M. Rogers.

He explains that Cape Lookout separates the coastal system into northern and southern provinces, each with a unique geologic framework that results in uniquely different barrier islands and estuaries. He characterizes the coastal system south of Cape Lookout as sand-starved, ancient “hard bottoms.” In contrast, the northern province is underlain by younger sediments, comprised of mud, muddy sands, sand and peat deposited during sea-level fluctuations. The barrier islands also differ in orientation to the shoreline, depth and width of the continental shelf.

Cleary is using high-tech instruments to collect data on the offshore geology to explain the impact of recent hurricanes on North Carolina’s coast. He wants to determine the role the underlying geologic framework played in beach recovery along various shoreline segments. Some, with abundant sand-sharing systems, recovered through natural processes.

However, many severely impacted areas are now at even higher risk due to the historical sand loss produced by the storms. He says that millions of cubic meters of sand were transported beyond offshore barriers, or onto the shoreface — most of which is permanently lost to the natural rebuilding system. With less sand available, the shoreline recedes.

The results of Cleary’s research will help determine the availability of sediments suitable for future beach renourishment projects. His results also will help agencies such as the N.C. Division of Coastal Management refine their management strategies in light of shoreline differences.

Looking for Effective Remedies

Some scientists have adopted a “let nature take its course” position in dealing with beach movement. Stan Riggs, East Carolina University geology professor, recently told a state legislative committee that urban-style development is no match for the dynamic nature of barrier islands. He warned that a Category 4 or 5 hurricane could “break up the Outer Banks.”

There are alternatives, says Spencer Rogers, North Carolina Sea Grant coastal erosion and construction specialist. He says that a well-designed beach nourishment project can be efficient, effective and environmentally friendly.

Working with beach communities to evaluate the impact of hurricanes Dennis and Floyd, he found the closely spaced storms destroyed 65 buildings between Currituck and Sunset Beach. Another 903 that were threatened by erosion were considered repairable.

Sandbags are permitted only as a temporary emergency measure. Photo by Spencer M. Rogers.

Rogers was especially interested in the fate of the structures behind nourishment projects at Wrightsville, Carolina and Kure beaches, where Floyd’s 75-year surge event occurred. These publicly funded nourishment projects, were designed by the ACOE for both long-term erosion and hurricane protection.

Each included higher elevation dunes and a wider beach. Not a single building behind these engineered dunes was lost.

Carolina and Wrightsville beaches are two of the oldest projects continually maintained by the corps. From 1965 to 1998, the Carolina Beach program has cost $26.3 million, while the Wrightsville program has cost $16.7 million. The figures reflect combined federal, local and corps funding sources. The Kure Beach program, implemented in 1998, cost $10 million for wider beaches, dunes, public walkover access and the extension of storm water outfalls.

Rogers says that recent hurricanes show that where sand is available, a well-planned and maintained nourishment program can be an effective option. However, the method requires a long-term commitment to add sand every two to four years. Nor is it the best solution for every erosion problem. It may not be cost-effective in areas with high erosion rates, or where sources of beach-quality sand are scarce.

Hardening of shorelines is not in the mix of remedies for the North Carolina ocean front, Rogers points out. Sandy beaches disappear in front of seawalls and bulkheads. Groins or jetties increase erosion for neighboring properties.

Cleary, Riggs, Rogers and Wells are members of the CRC Science Panel, established in 1997 in the wake of Hurricane Fran to help re-evaluate shorefront erosion rates and inlet changes.

While some scientists may find beach nourishment the more benign of the engineered erosion remedies, they demand continued, tough environmental impact standards for the CAMA permit process. Measures include monitoring the biological impacts of sand placement; monitoring effects on recreational and commercial fishing habitat; determining the suitability of the sediment to be placed on the beach; and ensuring public access to beaches.

Finding an equitable funding process for long-term beach renourishment projects can get sticky. The question of “who pays” often is a major stumbling block.

In March, Carteret County voters rejected a $30 million bond referendum to finance a 10-year beach nourishment project for nearly 17 miles of Bogue Bank beaches. The proposal called for levying a special tax in separate tax districts for oceanfront and non-oceanfront property owners. It would have been the first time a local municipality had completely financed a major beach nourishment project.

Adrienne Cole, executive director of the Carteret County Economic Council, explains that it was designed to be a stop-gap measure as the county moves through the lengthy approval process for a proposed ACOE project. Such projects usually take about 10 years from application to implementation, and parallel CAMA’s stringent permit regulations.

In the meantime, the county will move forward with a smaller project to pump sand from the Brandt Island sand disposal site onto Indian Beach. A portion of the county’s hotel tax will fund the project. Cole says, “I don’t think the county vote was against renourishment. Rather, it was more about the way this proposal was structured. I think that all citizens of Carteret County understand that this is a critical economic issue for the county.”

Retreat is Still an Option

Time was, that North Carolinians simply retreated in the face of the often powerful combination of nature: storms and the shifting islands, says Carmine Prioli, North Carolina State University English professor. Prioli is the author of Hope for a Good Season: The C’ae Bankers of Harkers Island.

The 1999 hurricane season wrecked havoc on Oak Island — washing away beaches, dunes, homes and roads. Photo courtesy of the “State Port Pilot.”

After the storm of 1899, residents of Shackleford Banks picked up and moved to the mainland, leaving the island forever. Now a wilderness area in the Cape Lookout National Seashore, the island is known for its wild horses and breathtaking maritime forest.

Other communities along the Outer Banks dealt with advancing seas and erosion in less drastic ways, Prioli says. They simply retreated up the shoreline out of harm’s way. A cottage industry of house movers actually grew out of the retreat policy.

In more recent memory, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse became an icon of the retreat policy, Prioli notes. The nation held its collective breath in March 1999, as the 100-year-old landmark was moved 3,000 feet away from the reach of the sea.

Relocation of buildings still is an effective option for some beach property owners. Between 1989 and 1995, about 250 buildings along the coast were moved landward either on the same lot, or to other lots.

“Retreat served us well as a policy for generations,” says Nags Head Town Manager J. Webb Fuller. It was a policy that most could live with – as long as the population remained low, and home sites were deep enough to accommodate the ebb and flow of the shoreline.

Much of the Outer Banks’ mushrooming growth took place between 1975 and 1995, decades of low storm activity. Now, building lots are smaller, houses larger and both are more costly. For many, there may be nowhere to move.

“We are constantly juggling erosion both chronic and catastrophic,” Fuller says. “As a community, we now are looking at beach nourishment as a policy that better fits the economic reality of today.”

He adds, “Sea walls or bulkheads are just not an option here. The beach is public domain. Once you harden the shorefront, you eliminate the public beach. We have, and the state has, always championed public access.”

Like his colleagues in the beach and shore association, Fuller would like a dedicated funding source at the state level as leverage for long-term management programs that have the greatest economic and environmental return for citizens and visitors.

“The state has a responsibility to its citizens to maintain its infrastructure,” Fuller says. “That includes roads, water systems and other assets. And in the case of beach towns, the most valuable asset we have is our beach. We can choose to ignore its maintenance needs, or to maintain it. If we ignore it, it will go away. So it makes sense to look at the quality of all our public resources.”

This article was published in the Early Summer 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.